Swimming in the Snake River

By Ryan Gossen

There are rivets up here in this eagle

there are box cars down there on your snake

and we are twins of spirit, no matter which route home we take.

-Joni Mitchell

My wife and daughter climbed out of the van in front of Departures. I put the emergency lights on and walked around for hurried, stressy goodbye hugs, then they entered the sliding doors of the airport. At first, I could watch them, pausing at the entrance, looking around for the security line. For the first time since summer began, they were in a world where I could not follow. Eliza would go home to start school. Laura would return to work and put the house back together. I would see them in a week, during which I still lived in this van.

Watching them leave my world, I felt a tear, and then an ache, and then I felt very light. I pulled on my seatbelt, set up the navigation and music on my phone, and headed back out onto Highway 99. The van felt like it accelerated faster. An old exuberant loneliness revved in my chest. I turned up the music and started talking to myself like a long, lost friend.

A hot, bright haze from fires in California had drifted out over the Pacific, then back across Washington, pushing over the Cascades. I drove up a long incline to a scenic overlook. I had stopped here once years ago and had seen all the way to Rainier.

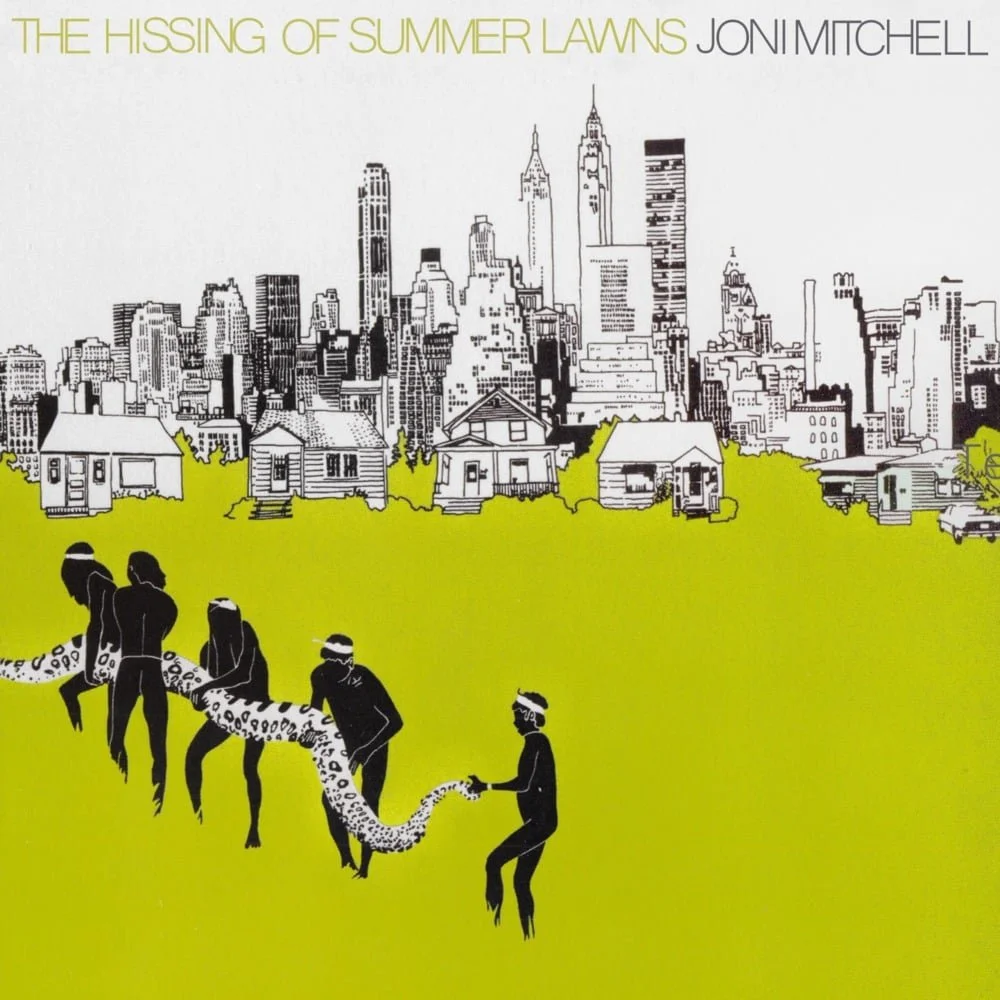

No one was admiring the view today, it was just a parking lot for idling semis with a commanding view of white-gray that revealed no forms and no horizon. The heat reminded me of Texas and I did my best to embrace it, since that was where I was headed. I was entering a deep, surreal Joni Mitchell rut, the albums after Blue, and began to infer elaborations of the abstract lyrics with strange, detailed stories from my own subconscious.

Eastern Washington is a high desert basin with sparse features, the subtle undulation of the land having been shaved down and planted in wheat. There are few creeks or drainages to be seen from the highway, and it's a surprise when the great Snake River appears, draining it all directly, a thin fringe of wetland contouring its edge.

The sun was low and it was getting late to not know where I would sleep. I pulled over to look at my phone. There was a park nearby, pinched between the river and farmland, about twenty minutes off my route. The dirt road was primitive and didn't feel like it was going to lead to anything but a farm. If this didn't work out, I would have to find the next place in the dark, which was not the experience I was looking for. There were no pull-outs, and I couldn't see how I would get around a vehicle coming the opposite direction without someone reversing a long way. The farther I drove, the less likely it felt I would encounter another person, and the more I felt that someone I encountered would be someone I did not want to see.

Back roads can be a great place to camp for the same reason they might be a great place to dispose of a body. Or a place where locals go to “blow off steam.” I've woken up in many back road campsites to find scorched Bud Lite cans and hundreds of shell casings around the fire pit. I love a good party, but some folks party differently, and finding a good campsite is as much a matter of when as it is where. The big sign, in state park font, with rules and hours can be so welcoming, such a relief from being in stealth mode.

No camping longer than 14 days.

Very generous, but who stays at this tiny park for two weeks? I imagined some combination of vehicle trouble and medical debt.

I turned down the hairpin and drove past worn patches marking informal campsites. Three were directly on the river, and someone occupied the middle one. I pulled up along their left, cut the engine, got out, and breathed in the river smell. My neighbor was a woman who had put up a tent and a blanket, where she sat cross-legged, facing the river. Before I parked, she must have been enjoying her solitude. I’m sure my giant white van and I changed the mood for her. I could go over and say hello, let her vibe check me, and then go about my business, but that might be misread.

From about twenty yards away, I waved. “Hi! Do you mind if I camp here? So I can swim?”

I held up my towel as proof of my intentions, as if swimmers with their own towels were more trustworthy. The vibe was weird.

She turned and said, clearly, “I’d rather you not. No.”

I stood there for a second with my towel and looked at her, then looked at the river just a few yards away. It was hot and my back hurt, but it appeared I had checkmated myself. Of course, she would rather I not camp next to her. I had thought that by offering a non-obligatory courtesy and gesturing with a towel, I would earn her trust and reciprocal courtesy.

I’m just no good at game theory.

Having asked, I felt obliged to honor her answer, so I got back in the van and drove down the dirt road that went above the river, past the park. It ended at a gate where there was no level spot to park without blocking the road. I tried to pick my way down to the water on foot, but the brush was incredibly dense and lush, as if making up for the hectares of farmland above. I returned to the van sweaty, the stink of the road now sprinkled with dust and scratched-up legs.

Should I try and talk to her again? There were no follow-up questions that made sense. I made a 13-point U-turn in the narrow road and went back to the park, going past her camp, and parked in a day area down by the boat ramp. It was not a campsite per se, but the van allowed me to be comfortable most anywhere.

I got my swimsuit, towel, and goggles, and walked down the boat ramp, where a family had set up lawn chairs in the shallows.

Two medium-sized dogs decided I was not welcome in their space either. They ran snarling at me, one lunged at my legs while the other hung back, ready to go after my entrails, should I fall. I jumped back like a matador, deploying my towel. It must have been a spectacle, but the mom and dad had the guarded reaction of dog owners who got into frequent confrontations.

I waited, literally held at bay, while they got their dogs onto a long rope tied to a willow without making eye contact or speaking to me. Their kids were unfazed, playing in the water. They had this place all to themselves before I arrived, but my supply of compassion for people who did not want to see me was empty. I tried to make nice and yet not show fear, like a seasoned tourist. All they had to do was keep their dogs on that rope and not touch my stuff.

Once I waded into the current, I felt safe. The water was cold, then cool, then just right. At a depth of three feet, the Snake jogged, clear over rocks and fronds of river grass. Through my goggles, I could easily keep my bearings and swam in treadmill-fashion, studying features on the bottom. After a few minutes, I set my feet to stand and looked around. The family was there, a little farther away. Who knows where I might end up if I let myself be carried downstream? I wasn't bored or tired, I felt safe in the current, safe from anyone’s fear of me, safe from dogs, safe from the shifting canyons of semi-trailers on the I-84 at night. The air on the surface traveled downstream with the water and contained its smell and, it felt, an excessive amount of oxygen.

In this river, I could release even the sense of myself, the world around me changing me at last, dissolving me as I traveled against it, sending me backward from where I was trying to go.

When I finally got out, I was not tired or sore or sick of driving, I wasn't anything.

I set up my camp chair between my van and the hillside, cooked and enjoyed dinner and a glass of red wine, then fell asleep with a book in my sleeping bag.

I woke up when the yahoos arrived after dark. Two 4x4s chose the most obvious campsite, directly on the river, next to the woman’s tent. Their lights were bright, their fire was big, and they got louder as they got drunker. That lady had judged me to be an unworthy neighbor, and that made me feel bad. I felt vindicated now, but I was also worried. I have many routines which I mentally rehearse when I park for the night in sketchy places with my family. I think through what I should do if, say, some drunk starts banging on the windows.

I think in advance so that if I'm startled awake, I won't be indecisive. The routines range from sharing food and water to doing battle with an ax and pepper spray. In practice, I've never had so much as harsh words with other campers. I drifted off, telling myself that if I heard screaming I’d get out and walk over there with the ax.

At dawn, they were there, motionless in their tents. It was quiet, the way campgrounds are when the residents drank heavily the night before. Cans were strewn about, the fire smoking in a wide, white circle. The blanket next to her tent, where the woman had enjoyed the sunset, would have been flush up against this mess, but she was gone.

It looked like she had never been there.

The river was flat and smooth, I had to look close to see it was still moving, the grass fronds waving under the surface. I swam again and got on the road. There were another twenty-five hours of driving between me and home. Maybe I could find somewhere to swim every day of this drive and say I swam from Seattle to Texas.

At that moment, my wife and daughter were waking up and smelling the house smell, looking around and wondering if the summer had ever really happened, if there had been all those rivers and forests, if there really had been a Dad. I buzzed with coffee and cold water as I started up the van, a rogue wave, a free particle, arcing in the gap between here and there.

Ryan Gossen is a writer living in Austin, Texas, where he also pursues dance, Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu, and climbing, and is an active member of Texas Search and Rescue. He has had many vocations, including user experience (UX) designer, experimental psychologist, construction worker, arborist, and ski bum. He writes mostly about man’s interaction with nature. More of his work can be found on his website.