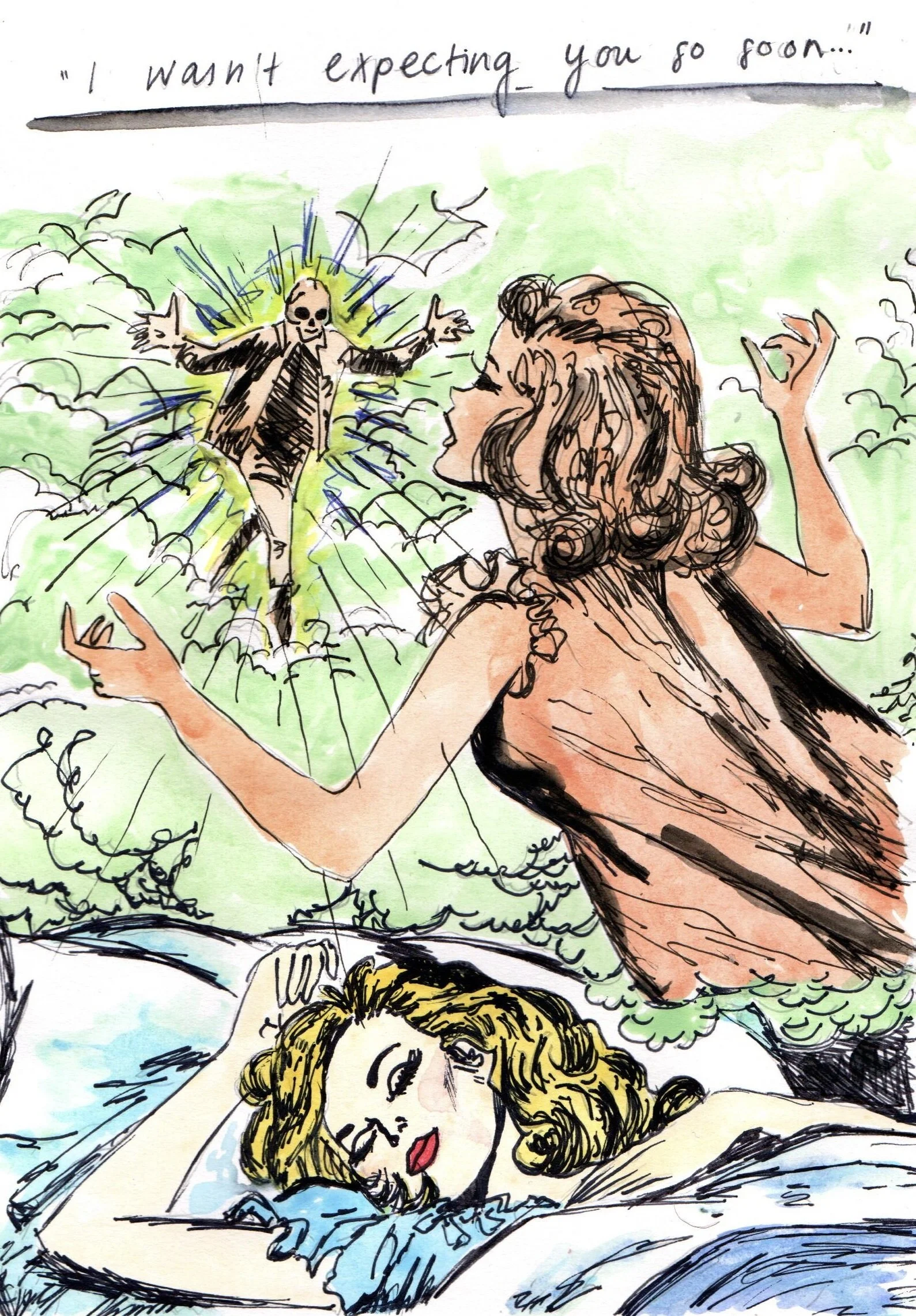

You’re Going to Die (Someday)

Writing and Artwork by Aoife Broad

Last Sunday my pantry was invaded by ants.

Well, not invaded as such – but overrun. Their little bodies marched up and down the shelves, seeking refuge from the floods outside; in search of something sweet.

Sweetness lay in two places. The first was a five-kilogram bag of sugar - which the ants dutifully carried piece by piece out of the cupboard; each granule dwarfing the tiny body that bore it away to some hidden nook where, presumably, their ant queen lay in wait.

The second was a pot of honey – which, being honey, was impossible to carry. I watched as the ants, in a single-file march, climbed one after the other up and over the edge of the honey pot, and fell to a sticky, golden, death.

Did the ants know that they’d die? Probably not.

But if they had known, would their behavior have changed?

As most readers are people, not ants; honey may not hold the same allure, nor the same sweet release. Yet other aspects of our lives do feature a similar stickiness, where weeks, months, even years of our time are spent in the pursuit of nothing.

Not an active nothing, not an active anything, but in the getting “caught up” with things. Whether it be a job, a project, or staring into the abyss of an all-consuming screen time (none of which are particularly enjoyable, nor do they provide any specific value to a life).

There’s an allure in bright, shiny things – so many of which surround, and even comprise our world today. Shininess, however, is deceptive.

A verse in the late Irish poet and playwright, Seamus Heaney’s 'The Salmon Fisher to the Salmon' describes this mutually assured destruction:

Ripples arrowing beyond me,

The current strumming rhythms up my leg:

Involved in water's choreography

I go like you by gleam and drag

—

And will strike when you strike, to kill.

We're both annihilated with the fly.

You can't resist a gullet full of steel.

I will turn home fish-smelling, scaly.

The prose annotates not just a man and a fish, but life and death itself. Heaney, the angler poet, searches for hidden enlightenment (Christ’s symbol was the fish) not with a spade or divining rod, but rather with pole and line. The poem’s ambiguity, particularly in the above verses, problematizes the analogy between speaker and salmon.

Man and fish are not so different after all.

If the salmon, like the ant, like humanity, knew his demise awaited (this time in shiny steel), would he swim upstream? Would he make a conscious decision to live differently?

While I cannot speak for the salmon, I can speak for myself. Some of this writer’s near-death experiences include:

Nearly being wiped out by distracted drivers on her motorcycle (x∞)

Getting caught in a quicksand-style bog while hiking (x2)

Car crashes (x2)

Twisting an ankle and falling off the side of a mountain (x1)

Falling into a crevasse solo (x1)

Dating an incredibly boring man for a year (x1)

(The last one was an especially close call...)

We know that living dangerously, or having a near-death experience, can cause massive changes in how we spend our time. Nowadays, I keep an extra eye out on the road and in the hills, and haven’t accepted any dates with anyone who’s ever mansplained vaporwave - a huge win.

But is it necessary to experience life on the precipice of death to change how we spend our days?

According to Scientific American, near-death experiences are triggered through singular, life-threatening episodes where the body is injured by a heart attack, shock, or blunt trauma.

While these circumstances sound decidedly unique, a lot of people who experience near-death share stories with a great deal in common: feeling painless, seeing a bright light at the end of a tunnel, detaching from the physical self, reviewing a Proustian highlight reel of one’s experiences (life “flashing” before their eyes) encountering existence beyond the ordinary.

Yet experiencing near-death holds both tales of wonder and of woe. While ‘wonder’ gathers the positive reputation; an affirmation of humanity’s interconnectedness with some form of the divine, the latter can be marked by intense anguish, terror, and solitude.

A unifier, bridging the divide between these opposing forces, seems to be that those who experience near-death are irrevocably changed.

But is near-death necessary to catapult truly transformational change?

… I don’t know.

Perhaps by dancing with death, an understanding arises. One that informs that neither the end nor the beginning (life itself) is to be feared. Without the static limbo of fear’s paralysis, life becomes more fulfilling, more connected, and less about the self.

If I died tomorrow, I’d be fine with it.

Terror lies not in the unknown, but in a life of stasis. Of days whose sole joys are found in the whirr of an office copier, or in the smile of a stranger on the bus. In lives where we forget who we are, what we stand for, and what we dream of.

Terror lies in a life wasted, in the pursuit of sticky, golden nothings - the new car, job, watch - over the people and things we love.

Today, it’s the 10th of August, 2021. I am 22 years old. Perhaps I will live to be 101, and live in three centuries. Perhaps I will live to 75, and die in my husband’s arms - surrounded by our family and fleet of King Charles Spaniels. Perhaps I will die in 10 years’ time, or 5, or this afternoon.

... It doesn’t matter.

What does matter; is how we live. The people we love, and the places we go. That’s what we’ll remember when we think of our time.

There’s no denying it - we’re going to die someday.

So why not make our time count?

Aoife Broad is a crappy vegetarian and artist based in Wellington, NZ. Follow her on Instagram @aoifebroad.